Passion and Commitment

Color. Texture. Beauty.

These ineffable properties provide the fuel for Preston M. Smith’s passionate commitment to abstract painting.

Philosophically and pragmatically Preston is gracious, open-minded, curious, funny and intelligent. As you’ll see in this far-ranging conversation, when he rummages about in his kitbag of tips for living artists, something intriguing, powerful and life-affirming is about to be revealed. The following key tenets resonate throughout our conversation, and he explores them at length.

Taking responsibility.

Viewing the world as a repository of abundant opportunities.

Finding happiness despite mercurial circumstances.

Transforming negativity into creative energy.

Adding value to any endeavor.

Being adaptive.

Doing what you say you’re going to do.

I have been a fan of Preston’s work for several years, and a devout listener to his podcast since its inception in March of this year. I wanted to talk with him and get his thoughts down in writing because I’m fascinated by the way human beings engage with creativity, and how any artist’s creative output interacts with her/his audience and our culture at large. I wanted to see his words on paper so I could study and engage with his ideas. Preston has also purposefully put himself on a path to be an educator, a mentor and an advocate for fellow artists. He’s intimately familiar with hitting the proverbial rock bottom. His insights about recovery and rejuvenation are inspirational. His astute observations about mindset and the practical nuances of making a living as an artist are well timed, given the challenges inherent in our culture’s “instant gratification and everyone else’s life is a curated fairy tale” vibe.

It is also worth noting that Preston is one hell of a good storyteller.

Preston and I spoke at length by video conference in early July of 2020. In a few places I have lightly edited the transcript for continuity, and portions that I have summarized for conciseness are marked with “[]” square brackets.

The Living Artist Podcast: Offering a Sense of Connection for Fellow Artists

Our conversation opens on the subject of Preston’s podcast The Living Artist: Don’t Wait Til U R Dead. He released Episodes 1, 2 and 3 on March 1, 2020 — “Welcome to the Show,” “Don’t Be a Jealous Artist” and “Art World Fallacies and Misconceptions” respectively. I was curious to dig into the history of his idea to produce a podcast, and more than that, his passion to share his hard-earned skills for coping with the realities of being a professional artist.

LH: The genesis of the idea for an in-depth conversation was… It’s interesting how this stuff all inter-connects. We’ll talk about your podcast here, and also a little bit later. I view the podcast as your interest in communicating to other artists and people who are artists in different domains—not just painting or sculpture—to convey more about mindset and thoughtfulness as opposed to your particular technique or what is inspiring you currently. It was this really interesting thing to me: metacognition. Where you execute, Preston, but you’re also thinking about the execution. But you’re thinking without thinking, so it gets a little bit slippery, and maybe not too “woo woo” to borrow a PMSArtwork phrase.

PMS: [Laughing]

LH: Because there’s a lot of power in you thinking about what you’re doing and putting that out in the podcast. You’ve expressed some of that in your interviews; printed and recorded. But I think that was a catalyst for this conversation, to get you in written form so people can read and study what I call this “fluid Master Class” that you’re giving through the podcast. So, here we are.

PMS: Thank you for that, first of all. Well, it’s one of those things where the podcast was a little bit scratching my own itch too, because I wish I had something like this when I was starting out. Not even starting out, when I was just building my business, my body of work. It would have been nice to feel like you’re not so alone, other people are going through it, you’re getting little tips and tricks here and there. Because being an artist can be lonely. I know we all thrive on isolation to an extent, but it can cross over to that negative side where you feel like nobody knows anything about you. You’re kind of lost in your own world all the time.

So, feeling that connection from time to time is important and I wanted to provide that for a group of artists. I’ve gotten some good feedback so far. The main thing for me is trying to speak as honestly as possible. Not editing myself. Not being too aware of what I’m trying to do, like you said, thinking about thinking. I’m trying to have an idea of where I want to go with it but at the same time have it be fluid enough that it’s almost semi-improvisational.

LH: Exactly. I’m glad you mentioned that. Because I can envision a codified set of Preston M. Smith’s Jedi mind tricks.

PMS: [Laughing]

LH: It would be a powerful thing. Right now what’s happening is—the snippets unfold, they’re extemporaneous, it’s clear that you’ve spent some time in your soul, your mind, thinking about—whether it’s fear or inspiration or fallacies in the art world—there’s so much we can talk about.

It’s clear that it’s well thought out, but the delivery is very—maybe this is kind of an O.G. expression—a “fireside chat.” It’s not a lecture modality or academic or clinical. It is where you as the podcast host say [to your listeners], “This is what I’m feeling about ‘what does it mean today to be an artist.’”

PMS: Right.

LH: You put down these touchstones and then I’m free to listen and extrapolate from there, and develop my thoughts about that. I think you’re on to something.

PMS: Thank you. I didn’t want it to be too didactic. I didn’t want people to think that they were being talked down to, lectured to. We spoke about this before at one point, about writing. It’s kind of a similar thing. They always say when you’re writing fiction it’s like you’re sitting down at a bar with one of my closest friends and I’m just telling them a story of something that happened to me, over a drink or whatever, and that’s kind of what I wanted the podcast to be. The podcasts are very intimate, which is great, that’s a great format. You could have an audience of 40,000 or 50,000 people, but it always feels like the person is speaking directly to you. You’re almost part of the conversation.

I don’t know if you’ve had this experience, but I’ve had this before where I’m listening to a podcast that I like and they’ll pause, and I’ve been so busy doing something in my day, I have this knee-jerk reaction that I’m supposed to interject something. Then I go, “Oh yeah, I’m listening.”

LH: You get to know the personalities and I want to say to the individual, “Fred, wait a minute!” I do find myself deposited right into the space where they’re talking.

PMS: Yes.

LH: I think there’s a power to that, distinct from, say, a video of the same phenomenon. Some of the podcasts both of us listen to, I’m sure are video. I have to say I’m not interested yet in watching the video of my podcasts that I really dig because there’s something happening about the auditory, your brain goes into a mode of receiving a story. I wonder what the brainwave patterns are doing, I really think there’s some neurochemical thing happening.

PMS: It’s weird. To quote Woody Allen, it enters on a different level or from a different orifice because when you’re watching a podcast, you visually—automatically it triggers things in your brain where you’re looking at how the person looks or what they’re wearing or the dynamic between the two sitting there in the room, or anything, the lighting in the room. When it’s just zeroed in on the audio, it’s much more powerful.

LH: Yes, and for me personally I don’t interrupt them. If I do try to watch a video feed of someone giving an audio podcast that’s a dual feed, I get easily distracted and my attention drifts. So it is more engaging and I think this does make a lot of sense. I found myself very interested in going back to different points in certain episodes and wanting to be able to [study the words]. Then I thought, “Well, I could ask Preston some questions and we can just write this down.”

PMS: Yeah!

LH: And it would be available for people to look at in yet another medium, which is the written word. They can think about the words in addition to having heard you as the person who thought of them—thinking them and speaking them. That’s the genesis of the idea for this conversation.

PMS: I love it. The written word, unlike podcasts, unlike movies or documentaries, it gives people a chance to pause and take their time with what they’re reading, what’s entering their body, and they visualize it in a different way. It almost allows them to interpret what you’re saying filtered through their own mindset. Which is great. You can get a little bit of that with a podcast, but it’s going. Once it’s going it’s going. Sure, you can rewind and you can slow it down or you can speed it up. But there’s something about the written word that is much more memorable.

LH: Yeah. We’re conducting an experiment and we’re about to find out here.

PMS: Cool. We’ll find out.

Origin Story: Rocky Mountain Vistas, Films, Music, Literature… Transmuted into Visual Arts

I believe that a person is who they are right now, right in front of us, and that their presence and thoughts in this moment are sufficient for interaction and connection. However, I also appreciate the power and significance of a compelling life journey and how it shapes us, so I was curious to visit the steppingstones of Preston’s early life as a kid on up to college and beyond.

LH: I do intend to come back to the podcast towards the latter portion of our chat, because I want to understand where it sits right now and where it’s headed and its genesis. I think it’d be interesting for people to have an understanding of your origin story—where you grew up. What I found by reading some of your bio press pieces was that I get Idaho and the Sawtooth Mountain range, and you mentioned some things about drawing in the car on these mesmerizing family trips. That connected for me to help understand your art and you as an artist. If you want to talk a little bit about where you grew up and some of those formative experiences, I would be very interested.

PMS: I was born in Denver, Colorado, a little suburb called Littleton. Then my family moved over to Wyoming. I went to school in Wyoming until first grade, then I went to Idaho and then I came back to Wyoming until high school, then I went back to Idaho. Then I went to college in Washington.

Growing up in Wyoming as a kid was amazing. As an adult I know it’s treacherous, the winters are hell, the wind is hell. My dad wrote a short story about the psychology of the wind in Wyoming. I grew up kind of isolated as a kid. My dad was an entrepreneur. My parents owned a chain of movie theaters and restaurants, and the movie business was always a very difficult business. My dad was traveling a lot and it was taking up a lot of his time.

LH: Like mom and pop or franchise? What types of theaters?

PMS: It was their own, called Rocky Mountain Resort Theaters. My parents set up a small chain of independent movie theaters in Park City, Whistler, Sun Valley, basically a lot of the resort towns they were interested in. But we first started out in Wyoming. Laramie, Wyoming. Cheyenne, Wyoming. My dad’s dad was from Cheyenne. I think that’s probably where I got my love for acting. We got to go to the movies for free. Some movies I remember going back to the theater and seeing eleven times. There’s a genesis of visual information from movies. I find that I’m not like a lot of painters that I know. I get a lot of my inspiration from different sources. Whether that be film, music, literature, whatever, but I transmute that into visual arts. I’m also inspired by paintings too, but I remember as a kid growing up saying, I want to be a stand-up comedian, I want to be an actor, I want to be an artist, I want to be a professional athlete. I was a basketball player, that was my big thing. So I was kind of torn.

My best friend and I, Ryan O’Malley, we made movies. We filled up four or five whole tapes of movies that we made—little sketches, artistic scary movies, we did all the makeup, we did all the action, we did everything. We even created our own Mad Magazine issues where we drew the whole magazine, put it together. But yeah, drawing in cars, I was always sketching as a kid. As I got older I was pulled in all different ways. Was I an athlete, was I an artist, was I trying to be an actor? My dad used to tell me, “Be careful not to be a Jack of all trades, master of none.” But I actually think that’s been to my advantage. There’s a podcast by Chase Jarvis [The Chase Jarvis LIVE Show], he talks about how now more than ever, “having the hyphen” is more important. You don’t have one craft or one job that you do any more; I’m this this this this and this. I think that actually served me well.

Gonzaga University and a Life-Changing Mentor

Teachers are woefully underappreciated and underpaid in our society. I can cite several teachers from my own journey through grade school, high school and college who changed my life in a positive way with their nonjudgmental encouragement. It’s heartwarming to hear Preston recount his experiences with teachers and mentors, and I’m willing to bet that their good example of helping their students—including him—contributed to Preston’s desire to encourage fellow artists.

PMS: Then we came to Idaho and I had a really great art teacher in high school, Mr. Blackman. I took four or five art classes a year and I got a chance to do a lot of stuff. Sculpture, drawing, painting, silkscreen, everything, you name it I did it. But I narrowed it down to what I liked to do which was draw and paint. They had little display cases in the high school and my work would make an appearance in there from time to time and that was some validation. I ended up going to Gonzaga University. I thought I was going to play basketball there, but I didn’t. I was going to walk on to the basketball team, but I decided I was gonna throw all my energy into painting and acting. I was kind of a double major of a theater actor and a fine artist.

LH: They had a theater program and a fine arts program?

PMS: They did. It’s not super well known for those programs, but they’re good. We had some great teachers. I met my mentor there, Robert Gilmore.

LH: Robert Gilmore. I thought maybe you ended up in Boston at some point with your education, but he was at Gonzaga.

PMS: It’s a small city, Spokane, Washington. Known for its basketball team, I think they made it to the Elite Eight for the first time, it was either my first or second year there. That put them on the map and that completely changed the whole program in town. Spokane at the time was also known for its serial killers and meth labs. [Laughing]

LH: You’re talking about multiple genres of input and experience. [Laughing]

PMS: To give you an idea, David Lynch got a lot of his inspiration for Twin Peaks from Spokane.

LH: So it sounds like in high school there were the beginnings of technique and exposure to a variety of different genres of art as in painting, sculpture, sketching, drawing, and that distilled down, even before you left high school, to primarily painting and drawing?

PMS: Correct. Then when I started to get more involved, in college I got into theater and I was in a band. We started a punk/ska band.

LH: 10 Minutes Down. [Preston was a founding member, lead singer and co-songwriter of 10 Minutes Down.]

PMS: The band had a lot of different iterations. We kind of parted ways when I was about ready to go to LA ¬¬because I think they saw that I was moving on. We had some creative differences too, but I was with them for about three or four years. We played the Vans Warped Tour. It was great. Music really fed me for a long time too, but I felt like even in college I was being pulled in different directions.

The Kreielsheimer Assistantship: Creativity Requires Work and Commitment

PMS: As college progressed I stated to go a little bit more towards the Art Department. Because I originally was going to be an Art Minor and then I thought maybe I can be a double major. I ended up graduating one credit shy of being a double major, but they still let me into the Senior Art show because they basically said, “You’re an art major.” My professor and mentor Robert Gilmore, they give this thing called the Kreielsheimer Assistantship. They give it to one student every year and they gave it to me. And I wasn’t technically an art major, so a lot of people got upset about that. [Laughing]

LH: You knew people in high places.

PMS: I guess so. [Laughing]

LH: That allowed you to kick-start the beginnings of an entrepreneurial art career? Like a grant or a scholarship? What is it exactly?

PMS: It’s an apprenticeship with some teaching aspects also. I worked with my professor. I helped him. I was an assistant teacher during painting and drawing classes. I had my own studio. I had access to all my own materials. It was wonderful. I stretched 150 canvases when I was there. But really I soaked up… Gilmore was an old-school Boston painter. He learned from one of the old masters and he came over here and he’d been painting for forty years when I met him. He had this great little studio on campus right by the water. It was almost like a Hogwarts type thing, it was a very magical corner of campus.

He taught me a lot about being an artist, taking it seriously. He was very knowledgeable. It was interesting because a lot of people couldn’t relate to him because he’d get lost a lot in his speech, “You know, art, to me…” then he’d look over your head and he’d trail off. But when you got him in the office, he would quote you the first page of a Tolstoy book, so we started talking about everything; literature, music, he was a big jazz guy. We were like-minded people.

LH: Would you say he was a Surrealist, Impressionist, was he more literalist?

PMS: Not unlike me, he started out doing still life and landscapes and portraiture. As he evolved he became an abstract painter, which is interesting because that’s exactly what I did. But he never taught that. He was old school. “We’re gonna set up a still life.” He was all about the lighting. You had to learn how to draw first. You had to learn how to paint realistically. Still lifes, portraiture. I was always fighting to throw some surrealism and some abstract in there. So I’d have to sneak in. He gave me the code to the building and I would sneak in late at night. I would go up there and I’d be all by myself in the entire art department and I would paint until 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning. He’d come in every once in a while and he’d see this surrealist piece and he’d walk by it and he wouldn’t say anything. Then he’d come back by a little later, “You know, Preston, that’s not too bad, that’s not too bad.” So I got a little validation from him there. He didn’t give praise lightly.

I would watch him paint. I would go into his studio. He was always telling me not to let people just come into your studio. You have to invite them in. It’s a very serious thing. He would take me to his studio sometimes. He had huge piles of discarded canvases. Just to see this guy’s body of work, he was so prolific. That was something that seeped into my bloodstream because I started painting like that too. I’ve got 900 paintings now and I’ve got a lot more in me, believe me. I watched him work and he worked every morning. He would get up before school and he would go in and he’d knock out a painting. Then he’d come teach. Sometimes he’d go back and knock out another painting. He was a real working artist. Kind of blue-collar, working artist, but he also had this nice university job.

LH: Was it mainly—was oil your medium in college or both oil and acrylic?

PMS: Oil. Only oil, baby, because a lot of the old school painters they didn’t take acrylic very seriously at the time. I’ve learned to love acrylic as well as I’ve gotten older. He taught me a lot about light and shadow. He had this little technique that he would use where, a lot of times you’re adding layers of paint but he would do this wipe-away technique where he would have these bold colors and he’d cover them with a darker color and then he would wipe away to allow the light to shine through the canvas. To be getting light from behind and it would illuminate these colors and it was beautiful. I painted like that for many years and then I started to develop different techniques as I got older, but he was a big inspiration to me. We kept in contact a bit but he wasn’t very good at communication, so I lost touch with him and he’s passed now. I wrote a big essay for him that was read as a eulogy at his funeral.

[Links to Preston’s eulogy “A Tribute to the Late Robert Gilmore” and a video interview with Robert Gilmore appear at the end of this article.]

LH: Sorry to hear that. Obviously, he was a person who became not just a mentor but a friend.

PMS: Definitely, yeah.

Color, Light, Depth and Alternate Day Strabismus

Before this conversation, Preston and I corresponded about color. By that I mean the physics of color, how the human eye and then the brain convert the wavelengths of photons into “color perception.” Wonky, yes, and I hope to explore this topic in the future with him in more detail. Here he talks about color, light and depth, and reveals something intriguing about his childhood.

LH: He was a big influence on you. And we’ll talk about color, and I don’t mean so much the physics of color—I know that’s another possible topic. You’ve expressed in a number of different interviews that I’ve read, how important color and texture and beauty are to you. Since we’re talking about color, do you think that that is where—I’m picturing the very picturesque settings in which you grew up. The light. I can just imagine the light in Sun Valley or Whistler or wherever you went, and how that wouldn’t be something an urban city person, artist, might experience light that way. Where do you see the genesis of your fascination with color? Of course, every artist, painter, is fascinated with color. But do you know what I’m getting at?

PMS: For sure. One thing I forgot to tell you, when I was young, too young to remember, I was cross-eyed. I had this thing called “alternate day strabismus” which is every other day I would be cross-eyed and the next I’d be straight. Very bizarre. I had no depth perception. Technically to this day I have no depth perception. It’s very weird. I had laser eye surgery when I was about three years old and they fixed my eye. When I get tired I still have a tiny bit of lazy eye. The doctor said I might have to fix it again as I get older, but I haven’t yet. I think that shaped—whether that would be subconscious or just through experience—that shaped my visual medium a little bit.

I don’t know if it shaped my use of color but I’ve always—like you were talking about with how people perceive color—I think it’s very interesting to talk about how people perceive depth perception. Because I’ve never really had it, so I don’t really know what I’m missing. But my visual interpretation of the world still looks like, to you, what a person with depth perception might have. Correct?

LH: Yes.

PMS: So if I’m doing a realistic painting or a pop surrealist painting and it’s representational to an extent, you can see the composition, you can see the foreground, the background, you can see the light and shadow that makes it three-dimensional, where does that come from? Is that experienced as light, as I’m experiencing light and shadow? I don’t know.

I played sports too. Baseball was very difficult for me, but I learned how to catch. I learned how to perceive a ball coming at me at rapid speeds, and now I can catch very well. I can tell still to this day that when it’s being thrown at me, I’ve learned how to guess very well instead of really seeing it into my hand. I’ve learned how to guess where it’s going to be and I’ve developed a different form of depth perception, I think.

LH: Maybe predictive more than cognitive, or something happened to self-correct and you became very adept at that process.

Intersection of the Mountains and the City Life

PMS: I know that’s not an answer to your color question, but I think that’s worth exploring because I think that has shaped me visually a lot too.

Color… I would consider a lot of my art as an intersection of the mountains and the city life. That’s been a big thing for me. When I first came to the city, you could see a lot of backgrounds in my surrealist work. You see mountains and hills and trees and nature but then you also see a very cosmopolitan figure or I have little outlines of cityscapes in the work too. It’s like this constant fighting between the city and nature. That’s always been something for me in my poetry too, but I think color for sure came from my experiences growing up. Going camping. My dad was a big fisherman. We grew up like A River Runs Through It. We were fishing every weekend. He was a fly fisherman and he taught us how to fly fish. Yeah, I’m sure subconsciously those vivid and vibrant colors were something that I stored away.

LH: Right. You participated in the Kreielsheimer Assistantship for about a year post-collegiate. What transpired next? Were you still living in Washington at that time, for that year?

PMS: Yeah. I graduated on time. Then I stuck around for another year and I worked with my professor and I was doing professional improv downtown also. I had a girlfriend at the time who was an actress. She started to graduate a little early so after my apprenticeship was up we were gonna move to LA, move to the “big town.” I was going down there to be an actor and a painter. She was going down there to be an actress.

To close the loop on my mentor. He took me out to dinner a day or two before we left. He bought me a dinner at this diner, I remember we had this great conversation. He said, “You know, Preston, you’re going to be an artist.” At the time I didn’t want to hear it, “Well, I think I’m going to do both.” He said, “No, you’re going to be an artist.” Like he was looking in his crystal ball, you know? It’s funny because I came down here and I did acting for a strong two years and I really liked it. I love acting. But I got so disillusioned playing the game and waiting for the phone to ring and going on auditions all the time. He was right.

The Big City, Restaurant Jobs, Poverty and Self-Discovery

Does toxicity originate outside ourselves or within? The answer is likely a mix of both, but let’s admit we tend to convince ourselves that our misfortunes are caused by the outside world; any source other than ourselves. In the ensuing portion of our conversation, Preston explains—with a no-holds-barred honesty—how he came to realize that changing his perspective about his adverse circumstances was the key to detoxifying. He reveals that by taking full responsibility for his situation, practicing self-care and committing to a “long game” attitude about his artistic career, he found balance and a renewed creative energy.

This section cites two prestigious, celebrity-studded events that Preston participated in during this self-described dark period. In 2007 he painted and auctioned off a live painting for the David Lynch Foundation. In 2009 he was commissioned to paint twelve portraits of President Obama for the Inaugural Purple Ball.

PMS: My girlfriend and I broke up. We changed, I guess. All of a sudden I found myself alone in the big city, and I had to move out of our place. She was shooting a movie when we broke up, so I made the transition into getting this tiny little studio apartment in West LA. It was probably 400 square feet. Moving all my stuff, my paintings at the time. It was a rediscovery of myself. It was amazing.

I was drinking a lot. I was working a crap job at a restaurant that I hated. I was reading Charles Bukowski every night. I started painting again consistently. Every night that I painted I had to build my studio up in my kitchen and then when I was done break it down so I could use my kitchen again. It was very formative for me. I started listening to Tom Waits. All this music and poetry and drinking and experiences. I had some really horrible experiences with women, dating in the Los Angeles scene with no money, being impoverished, it was great. Looking back on it, it was a very romantic time in my life, but it was an extremely difficult time.

LH: I know that was about a ten-year stretch where you were dealing with the restaurant job and that scene, really struggling to find the answer which—spoiler alert—it turned out to be abundance mindset and positivity, and letting that energy drive your art instead of, with no judgment on those… Charles Bukowski, a phenomenal literary talent. I’m not sure about lifestyle.

PMS: Oh no, he was a notorious drunkard.

LH: Self-destructive obviously. He was struggling to… I can’t presume to know what he was struggling with. The idea of the inner critic and being derailed so often by all of these fascinating topics you’ve picked for your podcast: fear, the absence of laughter, being crushed by your own interest in really understanding [one’s own existential angst], and then finally doing some self-discovery. That’s all happening towards the tail-end of that ten-year period [in your life], like 2012, 2013, 2014-ish.

PMS: Yeah.

LH: You got a lot of painting done and there were some opportunities. You learned there are two different ways to approach that. To be part of an opportunity and then to nurture it and allow it to carry you to another perhaps different or elevated place. Whether it’s the David Lynch stuff or the Purple Ball with President Obama. I want to dwell a bit on that transition into your “creativity from negativity” and now positivity, right? You want to talk a little bit about that experience?

PMS: That’s everything, really. It’s the only reason that I’m, first of all, probably alive. Secondly, that I’m with my wife. And thirdly that I’m a full-time artist, that I’m making a living doing what I love. Had I not made that transition, none of those things would have happened. But I do want to underscore one of the things you said.

The restaurant job, and this is important, and I’m not saying that everybody has to do this, but for me it was very important, you can call it stubbornness if you want, but I wanted to have a shit job that I hated. Because my dad was a serial entrepreneur, my brother went the financial route, got his masters and was a financial advisor. I know I could have done those things had I wanted to. But that was not me. I also know I would probably have been very unfulfilled. Life was not worth living to me if I went down those routes. I’m very serious when I say that. I had that struggle. My wife can tell you, when we first got together I was still, every day, in this existential angst of what am I supposed to do, am I supposed to do this? I tried other things. I had moments where I could try to sell insurance, or I could try this or that. I tried a lot of those things. I got my license for selling insurance and I worked for a buddy for a while, and all that those things ever did was make it even more apparent that I’m supposed to be doing this as an artist.

I forced myself to stay in these restaurant jobs for, if you’re including college, about 16 or 17 years. It’s a very soul-sucking job, especially if you don’t want to be doing it. I know there are a lot of people who wait tables, I want to be mindful of that, and some of them make really good money and they like it. For me, it was horrible. It was something that every time I put on the apron and walked to work it was taking a piece of me, you know?

LH: It was toxic.

PMS: It was toxic.

LH: It was unrelentingly toxic.

PMS: Yeah, because not only the job does not pay well, typically, and in LA where rent is so high, but you also have to—and especially in LA—you have to take a lot of shit from customers. It’s about something that’s so mindless. You’ve probably read my poem about waiting tables in my book. That encapsulates the whole thing for me. That poem speaks from my soul, because at the time, taking shit from people who would yell at you or belittle you because they didn’t get their free bread. Screaming across the room at you, snapping, “BREAD!” It’s very dehumanizing. I did that for that long and I told myself I’m going to keep doing it until I can make a living as an artist.

LH: I heard you say, “This is important.” At the beginning of this point in our discussion you said, “I was stubborn and I was going to have the shit job until I can make a living as an artist.” That was deeply embedded and I don’t sense that stubbornness anymore. It has turned into what I’ll call persistence and “doing the work.” Doing the creation instead of doing the “I’m in this drama triangle with my boss and the customers and myself…”

PMS: Myself, yeah.

LH: “…and I’m not gonna get out of it because…” What do you think was feeding that monster? Did you think that you had to be the tortured artist?

Feeding the Monster: Am I a Tortured Artist?

PMS: Definitely. There’s a huge stigma in the world about that. That feeds into the podcast later. We’re taught as artists that we’re not going to make any money. It’s this romantic lifestyle where you just isolate and you create and you drink. You’re not supposed to be successful, essentially. But I can tell you exactly where it all changed.

I got so tired of hitting my head up against the wall. It was partially out of necessity that I had to change, because I was going down a route that was not sustainable. Part of it, yes, was drinking. That’s part of the culture of working in restaurants too. You go out every night afterwards, you drink. But I was pushing it further and further. I was staying up until sometimes six in the morning with people. It was becoming this vicious cycle of hangover to work, work until you feel better, to drink again, hangover, that kind of stuff.

That, in a weird way—and this is why I think this is important to talk about—when you have a job that’s that bad, you’re that unhappy with your life, you put yourself in that situation because what it does is it makes it very myopic. All I’m focused on is getting through my shift. That’s all I care about. Getting through this hangover and my shift so I can get out on the other side and then go drink again and feel better about myself. I feel for people who are still in that cycle because it’s almost an impossible cycle to break.

LH: It’s that pattern of addictive thinking. Fortunately for you and all of us who enjoy your art and you as a person, you found a way to break out of that cycle and recognize that the eventual end result was going to be pretty cataclysmic, and would you be able to even function creatively. Aside from those bursts of creative energy, I know you spoke of that and that can happen. But the cost, the weight of the baggage was such that you sought some… you did a little bit of like Eckhart Tolle, you kind of did a spiritual walkabout. I know you didn’t leave your restaurant job because… fascinating and to your credit, you turned the corner and you approached giving your notice in a way that was the high road.

PMS: Yeah. That’s exactly right. That was where it all changed. I think a lot of people daydream about throwing the apron down in the middle of the shift and, “Fuck you, everybody, I’m outta here,” but really for me it was about making peace with it. That was the main thing. First of all, I made peace with myself. I hit a wall. All these things were converging. I was getting older. I had shame about working at a certain age still in a restaurant, taking shit from people. A lot of people I know in the restaurant industry are pretty young, they’re actors, they cycle in and out. I was one of the older waiters. That gave me constant shame. Which is stupid but I had that. It was self-imposed. I was also drinking too much, which was making me feel worse, which was damaging my relationship with my wife. Luckily she stayed with me and was one of the catalysts for turning this around, but really it was me doing self-work.

I had a co-worker who gave me some words of wisdom. It sparked some stuff in me like reading Eckhart Tolle, doing some self-reflection, stopping the self-medication. Not becoming more childlike but being more forgiving of myself and seeing myself through a child’s eyes which allowed me to forgive myself for certain things that I had shame about, which when you step out of it really aren’t that big of a deal; a lot of people go through these things, but for me it was huge. I had the weight of the world on my shoulders.

LH: It was your existential angst and your soul-crushing routine. For sure we can sympathize with people who have much more horrific circumstances.

PMS: Oh yeah, definitely.

Exiting the Angst: Not Too Woo Woo, Well… Maybe Just a Little

LH: The lesson here is that not only did you explore… Through self-exploration, you began to actualize it and began to incrementally see—not only as an artist but as a human being—this is a better thing, because I’m now more free.

PMS: Yes!

LH: I’m stepping out of the framework and if I need to leave this job I can do so with integrity. I want to explore being an artist full-time. I can approach that now with some equanimity which you did not have before.

PMS: Yeah, definitely. It all culminated into—I think about a year before I quit my job it was all of a sudden—it wasn’t like this every day, it wasn’t like “ahhhh.” [single-note chant]

LH: Woo woo. [Laughing]

PMS: Yeah. [Laughing] I was at peace. All of a sudden a lot of the crap I was dealing with day to day in my job, people who came in. Eckhart Tolle talks about the pain-body. These pain-bodies wanting to fight with each other. My pain body was gone all of a sudden; they would try it and it wouldn’t go anywhere, it would kind of dissolve. I watched this happen all the time. People would come in who used to be “problem” customers, and I got along with them fine. There were no problems. My attitude started to shift, and I quit drinking.

Although I’m proud of myself on one level. I did this thing where it wasn’t like an AA thing, although I did go to a couple of AA meetings but it wasn’t for me. I can still drink now, to this day, and I will drink every once in a while. I did this Princess Bride approach, you know where he inoculates himself, the part where he takes the iocane powder? [Laughing] I did that with drinking.

Our bar was transitioning into a gastropub and we were encouraged to sample all the beers every day so we could tell our customers about it. For me, who was quitting drinking, that’s not necessarily a very good thing, but I decided I’m going to inoculate myself. I’m gonna sample these here and there a little bit at a time. And I was like, “I’m good.” Over time I started to not want it anymore. I could taste it, I’m fine, and then I would never drink at home, I would never go out anymore, I changed a lot of my friends and my lifestyle. But now when I go out with people, I can have a drink or two, I’m fine, but I actually prefer to not drink now. Which is funny because when I was in my Bukowski days—this is part of the reason why I related to him so much, because he was always doing those shit jobs, working at the Post Office, “Puttin’ my arms down,” [Preston’s Bukowski impression] that sort of stuff. I related to all of that so much. I remember in a poem of mine saying at one point, “How can you trust somebody who doesn’t drink?”

And now it’s funny how I’ve turned the corner to a point where—I’ve had plenty of experience with drinking, more than I care to talk about—but now I actually don’t want it. I know it’s going to derail anything I do or try to accomplish in my life, and my wife is beautiful, she doesn’t drink either. She didn’t do it for me, she was already transitioning out of that. We made this great evolution out of the drinking culture and now we’ve been so focused on things that we want to create that are beautiful in our lives, so that was what it was.

By the time I quit my job, I came up to my boss and I said, “Hey, you know, I’m really sorry but I’m making a transition out to being a full-time artist.” He was very nice, very gracious about it, and he said, “We’re proud of you and if you ever want to come back, the door is wide open.” And that was it.

LH: Excellent. To close this loop, I believe at this time you were beginning to experience the benefits of this incremental approach to putting your work out there, allowing it to fulfill the creativity instead of the tortured artist meme, and that there were some new habits developing. And you began to see in your own sales and your success as an artist, it started to manifest itself in some really observable ways.

Wake Up and Take Responsibility

LH: There was an overlap between the interest in self-discovery, taking the action—this is important for our readers—you didn’t just dream or think about it, you took action. Incrementally these actions created a new energy of positivity. It reflected in your artwork. It reflected in your personal life, your marriage, your job. Now you’re going to speak to that and talk a little about surrealism to abstract.

PMS: It’s one of those things where it almost feels like a conspiracy in the art world. They perpetuate this stigma of the tortured artist or the starving artist. Almost to keep you out. That’s the way I felt when I was coming up. I wasn’t always just at home drinking and painting. I was in shows. I was pounding the pavement a little bit here and there. I just didn’t know how to do it. Same reason why with the Obama thing, it was great, I was on cloud nine, an extreme high and then all of a sudden I was back working my job the next day, “Oh, okay, nothing happened.” I didn’t have the tools to know what to do, how to transition out of my lifestyle at the time.

They didn’t teach it to me in school. You don’t ever hear about it from anybody else. No other artists share these things with you. It was me getting off the sidelines. I got tired of waiting for somebody to… now look, you have to do the work. I always tell artists to develop a body of work first. I think a lot of people nowadays they want to jump right into the marketing, Instagram, social media, without even knowing who they are as an artist first, so I’m glad I had all that time of self-discovery and building my body of work. I got to a point where okay I’ve got to fuckin’ sell a couple of these things now. I’ve got like 500 pieces, and this was back then, in this tiny place, and it’s just not sustainable.

I was beating my head up against the wall at work too. I decided I have to start taking some responsibility for getting my work out there. A lot of this coincided with me having a spiritual awakening of sorts and re-discovering that I can be a happy person and I can not take myself so seriously, and still be a serious artist at the same time.

LH: Right. Because the seriousness—and you spoke of this in your podcast episode “Are You an Artist?” The seriousness I took away from that episode, you mean a commitment to the level of, “I can’t NOT write my poetry.”

PMS: Exactly!

LH: “I can’t NOT make music.” “I can’t NOT paint.”

PMS: Exactly.

LH: And that maybe was the beginning of an awakening that you’re going to pursue this both spiritually and commercially.

PMS: Yeah. It’s also, a lot of artists, especially back in that time, they believed their own myth. This whole myth of, “I’m this artist. My work is so important that somebody will discover me, they’ll pluck me from the field of artists. Then I’ll have my day in the spotlight.” Well, that doesn’t happen. If they don’t know who you are, if they don’t know where you are, if they have no means of seeing your work, it’s never gonna happen. So, it was a little bit by necessity. But it was also because it’s just not fun being like that. It’s not fun being tortured and believing so strongly in your own mythology and being this tortured, dark person all the time. I started to not take myself as seriously. It was nice. It felt like a weight lifted off my shoulders. And then, ironically, I was able to get some shit done too.

Flashback to a Decade of Soul-Crushing Debt

PMS: To go back a tiny bit. I had appendicitis at one point. I believe it was partially due to my lifestyle at the time. I went to work. I was forced to go to work. I was doubled over, I couldn’t work, they sent me home. I was laying on the street, it was that painful. I had to wait for my wife, she was my girlfriend at the time. Her mother was visiting from Argentina and they picked me up and took me to the hospital, because I couldn’t afford to call an ambulance. I went to the hospital and I stayed in the waiting room for three hours before they’d even see me.

Finally they got me in and they took my appendix out. I woke up in Brotman which is no longer there anymore. It was a very apocalyptic scene, Lee. They had a power outage at one point and it was like a zombie apocalypse movie. They had the green lights flashing and there was nobody in the entire hospital, and I was sitting in my bed hooked up into the IVs.

The point is, I got out of that, and I had insurance at the time because I’d always learned you gotta have insurance for a catastrophic event. I had Blue Cross forever. They denied me. They said that I had a voluntary appendectomy. They wouldn’t cover anything. They were going to charge me $27,000 or $28,000 which at the time might as well have been a million dollars, for someone who’s making $18,000 a year at a restaurant. Everybody told me I’d have to file for bankruptcy. I fought it. I appealed it. They denied my claim. They denied my appeal. Finally Brotman, the emergency room, came in and appealed it. Look, he came to the emergency room, we had to get his appendix out, we’re not paying for this. They got it down to about $7,000.

LH: Which was still half a million dollars!

PMS: Exactly. Half a million bucks. [Laughing] I had to do some negotiating. For the next four years, I told them I will pay this, I can’t pay this right now but I will pay you $100 a month until this thing’s paid off. That was a lot for me at the time. I’m literally living shift to shift. I got it done after four or five years. There was also $6,000 or $7,000 of debt I had from painting materials, my car broke down, I racked up a little bit of debt because of that. You can’t afford to live in LA if you’re a waiter. I decided that the first step for me to becoming a successful artist is to get out of debt. So I paid all this down. I decided I’m gonna make a sacrifice and I’m going to stop paying my insurance. I’m going to not have insurance for the next two years. I was paying like $250 a month, it was ridiculous.

LH: Pre-Obamacare.

PMS: Pre-Obamacare, yes, exactly. I decided that I was going to put all the money I was putting towards my insurance instead towards my debt each month. I’m gonna cross my fingers. I was still drinking, yes, but I was keeping in shape, I ran every day, I ate well. I put $250 towards my debt every month and within about two to three years—and I started selling some work—I got out of debt. This was something, Lee, at the time, I don’t know if some people can understand this, but I felt like I was gonna be in debt my whole life. I felt that it was going to keep growing and crushing me little by little, incrementally, every year. That was the first step actually, to getting a breath of fresh air. Feeling like I was moving towards something.

LH: And a sense of control over your situation.

Learning the Ropes of Online Art Marketplaces

Preston’s most popular podcast episode to date is “My Favorite Online Art Marketplaces” released on March 26, 2020. If you are a painter and want some practical advice about these marketplaces, I strongly suggest you have a listen to his quintessential review of how to use these platforms to hopefully increase exposure of your own work. The Article Notes section at the end of this article includes a link to his podcast’s landing page.

PMS: Definitely. I got out of debt. In the meantime I had decided that I was going to use all my spare time when I’m not working at my shift, when my wife’s at work during her day job, I’m gonna use all that time and I’m gonna transition into this whole online marketplace thing. I’m gonna cut out the middleman. I’m gonna stop waiting for this magical person to come out of the sky and give me my magical gallery that’s gonna fix all my problems. Which by the way, a lot of people get that magical gallery and they still don’t sell enough to make a living.

LH: So you’re going to switch from your primary marketing emphasis on real galleries to more online, virtual.

PMS: Correct. I didn’t say I was gonna cut off 100% galleries, I’ll still do them, it just wasn’t going to be my primary focus.

LH: Right. You were transitioning to explore—you weren’t throwing the baby out with the bathwater, because we know from your podcast that there are lots of benefits to galleries.

PMS: There can be. But my experience in LA and the gallery world was, you get in a group show from time to time, you ask all your friends and people to come. They go and see you. You don’t sell any work, or you sell a piece maybe. It’s $300, great. Rinse and repeat, every two months or so. It’s nothing. I remember feeling like this was insurmountable. Coupled with the debt and this idea of having to build my way up through the gallery system. It was a fairy tale. It was never going to happen. I couldn’t even see the steps to making that happen. I couldn’t see it. I couldn’t visualize it. It was all counting on this magical set of circumstances happening.

With getting out of debt, I’m going to apply that same type of outside-of-the-box thinking, I’m going to cut out the middleman here, I’m gonna start taking control of my part and my marketing. I learned marketing. I started developing a habit of every single day I’m putting my work up. I’m photographing a work. I’m taking all these different shots of it. I’m learning how to do it in Photoshop. I’m putting it up on an art marketplace. I’m learning what I have to do with each marketplace, Like-ing other people’s work, being present, all the stuff that goes along with that. It was basically what I do now, but without going to my job after noon. Now I paint.

LH: Okay. But you were still working in the restaurant.

PMS: Exactly. I was doing that while I was working at the restaurant. I’d put on the waiter cap and I’d go to work. But what started to happen—it wasn’t that it happened like this [finger snap]. A lot of artists want that to happen now, but I always tell them, “You have to play the long game.” I saw—I had a goal in my mind. I knew it was possible. Look, I lost hope many times, Lee, and finally there was this one day I remember, I think it was my mom’s birthday or my wife’s birthday, it was one of the two. At the time I was having spurts of not drinking and spurts of drinking, and I drank the night before and I woke up feeling horrible.

LH: And it was mom’s birthday!

Preston’s First Online Art Sale: “This Is Possible!”

PMS: Yeah, exactly. She’s in Idaho, she wouldn’t see me, but I remember looking at the phone and there was a text message I didn’t recognize. It was from Artfinder, “Congrats! You’ve sold a piece of artwork.” This was my first online art sale ever. It was $1,600. I was, “Whoa! Okay, this is possible!” [That piece was Day Tripper, 2016, shown below] I had to figure out a bunch of other stuff. I had shipping problems and all these things, but the point was, it all of a sudden became possible. This was the fruit of my labors so far. Now I’m not gonna rest back like I would in the past where you have one successful show and then you sit back, “Okay, well I’m good for a while.” That day I just kept going and I ramped it up and within that year or the next year I made like $15,000 in online art marketplace sales. This went from selling a piece every once in a while—maybe $1,000 or $2,000 a year—to $15,000 in my spare time. So now not only was I out of debt but I had a little bit of a safety net, which I’d never had before.

So I had this plan going the whole time. I’m gonna do this. I’m gonna give this a year. See if I can continue to sell regularly. Learn as much as I can. Balls to the wall. Then if I’m still doing it, and I had a goal of saving up $10,000, because at the time that would have lasted me half a year. If I’ve got a six-month cushion, I can burn the boats. I hit that goal after a certain time and that’s when I gave my boss my notice. It was a big jump. $10,000 as you know in LA is not a lot, but it was enough to make me feel like it was possible. That’s the transition out of it.

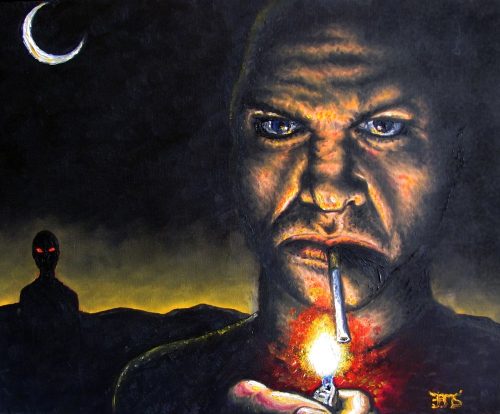

A Dark Pop Surrealism Period with Light at the Far End

PMS: If you want to talk about the transition from dark to light. The pop surrealism that I was doing for years, for ten, twelve, thirteen years, was all a direct representation of how I was feeling inside. It was dark. Some of the backgrounds were very light and bright, that’s how I transitioned into abstract. But the theme of a lot of these were extremely dark. They were like Bukowski poems embodied.

LH: I’ve seen a lot of that work and I know what you mean.

PMS: Yeah. It was very personal. I had a lot of self-portraiture. People would come into the restaurant and say, “Oh I love your work, but I’d never want to hang it in my house.” [Laughing] As this whole thing started happening—the transition, getting out of debt, getting with my wife, spiritual awakening, starting to feel like I’ve got my life under control—and I could see a light at the end of the tunnel as far as making a transition to being an artist for the first time. I started to become happier. My wife and I, we transitioned to being vegan at this time. Everything was becoming better and more positive. It started to show in my work. All of a sudden I was starting to do abstract work. Vibrant colors and texture and happy stuff. It was a direct representation of the transition from darkness to light that I was feeling in my personal life.

An Abstract Transition

LH: You began to produce more abstract work, or would you say there was a day where no more surreal or figurative and just abstract? Was it that binary?

PMS: That’s a great question. The painting Elements and Dreamscapes that you used for your wonderful poetry book, that was one of those paintings in that period of transition. I was doing a bit here and there, piecemeal, but I felt this pull towards abstract. It was like I was trying to hold on to the past a little bit when I was doing pop surrealism. “No, you still gotta exercise this muscle, you don’t want to lose this.” But the whole time my body was screaming, “Abstract art! Abstract art!” So that’s what I did. It was a little bit of a transition. I think maybe six months.

LH: Okay. Because that particular painting to me embodies a theme of positivity.

PMS: Yes.

LH: I think it’s whimsical and childlike and it speaks to a concept you’ve mentioned in a couple of different interviews about “experimenting like a child.”

PMS: Yes.

LH: I think that, gosh, it just clicks for me that that would be a transitional piece.

PMS: Yeah. And it’s one of my wife’s all-time favorites that I’ve ever done too.

LH: Then you were able to begin to explore both the application of your positive life energy as it’s reflected in your art, and you’re selling more. You’re seeing that there is a repeatable earning potential, commercial potential, with online art marketplaces. Selling through these marketplaces has become not your sole focus, but it is an important part of your marketing strategy, would you say that’s correct?

PMS: Definitely. Online sales from these marketplaces, not including my website, account for about 50% or 60% of what I make.

LH: It’s much less of a usurious commission than it would be in a real brick-and-mortar gallery?

PMS: For the most part. Although I will say there a lot of new art marketplaces. One of my favorite ones that I’m doing well on now, they take 50% like a brick-and-mortal gallery. But I think it’s because people are starting to really see the value in online art, especially now with what’s going on in the world with Covid-19 the virus-which-shall-not-be-named, they’re seeing how powerful online sales can be.

LH: More eyeballs. I mean, orders of magnitude more people would be able to see the works in that marketplace’s portfolio—your work and other artists—and they can obviously thereby avoid going to the brick-and-mortar gallery. I mean in six months I don’t think that’ll be a particular detriment.

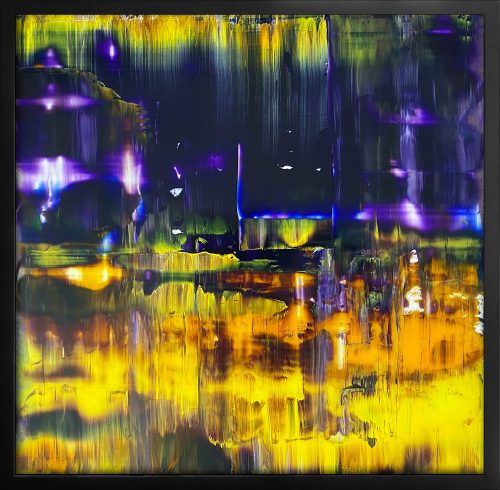

The painting Breakthrough (shown below) reflects Preston’s more current work, coming after his “dark pop surrealism to abstract” transition period.

You Have to Be Adapting, Always

Now we’re at a point in the conversation where Preston highlights a cornerstone in his life/work philosophy: adaptation. The dictionary definition of the verb “adapt” is “to make fit (as for a new use) often by modification.” He describes how adaptation freed him from the constraints of being mired in outmoded, inefficient ways of accomplishing his goals. Furthermore, he stresses the importance of proactively looking ahead for the next opportunity to adapt, rather than idly waiting until you’re forced to change, or, worse, remaining stuck in the past. Preston says, “You have to be diversifying and adapting, always.”

PMS: Can I say one thing before I forget. It’s kind of an underlying theme here that we’re not talking about yet, that I’m very proud about is adaptation. Because what I think I was doing in the past and what I think a lot of artists are still doing now, and what reminded me of this, we were talking about the galleries, I think a lot of them held on so strictly, “No no no no no no! We’re staying with the brick-and-mortar, we’re staying with this because this is what we do and this is where we’ve made our money.” It’s not a lot of foresight to where the world and where e-commerce is taking the art world.

When I started making this transition, I decided, okay I haven’t been very good at this, I’m going to start being malleable. I’m going to start adapting. I’m gonna start looking for new trends. I’m not saying I’m gonna paint certain trends, I’m saying different art marketplaces, certain apps that are coming out. Different ways to get eyeballs onto your work. That’s very important. Because I’ve gone through so many different stages of art marketplaces where an algorithm shifts or an audience shifts or one of the marketplaces goes out of business, and if you’re putting all your eggs in one basket, that’s gone. You have to be diversifying and adapting, always.

I struggle still with some of my best ones. For example, one of my favorite marketplaces has changed and now I’m trying to figure out a way to navigate that and change with that, so it’s a constant thing. But if I had been as strict as I was in the past, saying, “Nope, this is what works and this is what I’m doing,” or “This is what doesn’t work and I’m still gonna do it” [laughing] then there would’ve been no way out. I think adaptation is major.

His Podcast’s Gestalt: Ideas, Interviews, Creativity, Inspiration and the Long Game

LH: You’re looking forward for opportunities to adapt, so that’s a hyper-application of adaptivity. You’re saying, “I’m gonna be ready, maybe I’ll even explore my own…” I mean podcasts as an example, clearly it’s connecting with a lot of people. To combine that with art and the discussion of your ideas about creativity and inspiration, along with the interviews, it’s a very eclectic but effective melding of topics. Because I often want to know, “Terry Gross, tell me what’s happening behind the red curtain!” I want to know, right?

PMS: Yeah, definitely.

LH: What’s the chatter off-mic? You’re providing that and also access to your own thoughts and ideas, which have clearly brought you success.

PMS: Well, this is something that I couldn’t have done ten years ago, I couldn’t have done it five years ago. I couldn’t have done it three years ago. It’s a theme that I talk about a lot with people who ask me questions on Instagram all the time. “You’re just not there yet. You have to keep doing it. Doing the long game. You’ll know when you’re there.”

I’m still growing and learning. Hopefully ten years from now I’ll look back and go, “I can’t believe I was doing this.” But this took me eighteen, twenty years, to feel like this is not something that I have to force out at this time. It’s second nature to me. All of these experiences are very tangible to me now.

LH: Yes. I think “long game” is something that I picked up on, you’ve mentioned it in a number of different articles and interviews. That’s an important lesson both for aspiring artists of any stripe and for even veteran artists who might be struggling. Because, for whatever reason, sales might be in a downturn or everything can become a Groundhog Day grind. Realizing that it’s a long game and being satisfied with being in the moment of creating that next painting or refining your marketing technique or even something as logistical as improving your shipping mechanism. All of those things do create this gestalt of PMSArtwork. [hand clap] This guy’s real, it’s happening, I’m gonna get the painting, it’s gonna show up and it’s not gonna be improperly shipped and so on. Because commerce is driven by experiences that go beyond just, “That’s a cool painting,” right?

PMS: Exactly. You’re exactly right. That’s why I’m now thankful for my time in the restaurant industry because I’ve learned customer service. I know how to deal with that. To this day I think I have one of the highest-reviewed shops on Artfinder because I’m efficient, I’m fast and I will keep in touch. You have no idea how many people say, “The artist never even wrote me.” They say, “I got an order and then the painting, it just arrived one day somehow magically.” That’s not a way to run a business.

I think that “business” is a dirty word for a lot of artists. But in this day and age if you want to survive you have to look at it like an entrepreneur, or at least as somewhat of a business. If you’re fine with being the artist that’s in the shadows, creating your work, and not getting out there, you’re the pure artist who hasn’t sold out, whatever that means, that’s fine. But if you want to actually make a living, you have to develop some other skills. I think a lot of people use that as a rationalization nowadays to be, “No no no. I’m a ‘pure artist.’” That’s not necessarily true.

Discover Me: Nope, Discover Yourself

LH: I think you’ve done a good job of dispelling the fog of that myth, that meme, and that coupled with—let’s call it Discover Me. “Hey man, I’m a great musician, poet, painter… Discover me.” Let’s be pragmatic. Rarely does it work that way and unfortunately, and we haven’t touched a lot on social media, but one of the downsides of social media—the upside being all the incremental eyeballs—the downside is creating this false reality or reality distortion field where things happen magically. But when you sell the painting, you’ve got to package it, ship it, you’ve got to take care of the customer, communicate with them. And curate, nurture, develop a relationship with that person because they could be a collector. They could be a collector waiting—it might be a $35 print of Elements and Dreamscapes but the next year they’re gonna buy that $1,600 piece. I know you know this and I’m preaching to the choir.

PMS: You’re absolutely right.

LH: Many artists and authors and musicians, often we fall into these memes and I don’t know where they come from, Preston, but I’m grateful that you’ve put them out there and helped dispel them. I think that’s really cool.

PMS: Thank you. Do you know how many collectors I’ve had who bought a micro painting for $70 or $80, and I treated it the same way I would treat a $4,000 painting that I’ve sold. I give the same presence when I’m packaging. I write them a hand-written note. I treat it exactly the same way. I package it meticulously. I get it to them right on time. I communicate with them. Some of those people have come back and bought five, six more paintings, and larger paintings. I’m not saying that that’s the only reason I do it. It has to be, sure, it is business, but at the same time I just believe in that. I believe that you should treat everybody with respect and be grateful that they’re honoring your work by buying it and collecting it. And if something comes out of it later, that’s a bonus.

LH: Yes. I can relate to that because “transactionalism” is a big negative concept these days politically and policy wise—public policy. But I think viewing a transaction as a bridge between two people, if I’m the buyer of that micro painting, and you approach it in that way, I’m going to gravitate towards—I feel confident that this person [the artist] can handle that three by four foot painting that’s gonna need some special TLC when it’s getting shipped.

Adding Value

PMS: Yeah. Also, I don’t even look at it any more as transactional. I look at it more as you’re adding value. Somebody wants your work because it’s going to beautify their room or they want to get into the collecting game. Maybe it’s even they think you’re going to be worth money someday, who knows? But whatever it is, it’s value. You’re adding value. If you can take it seriously and you can be efficient and you can treat them with respect, then hopefully you have a collector for life.

LH: That all makes good sense to me. I know for me and my early life and childhood and grade school, high school, my parents taught me to be respectful of everyone and to be attentive and you know, honey always wins over vinegar.

PMS: Yes.

LH: To approach things like eyes wide open but also, “Hey man, how can I help you?” There’s a mutual respect so I think you’ve got that cookbook formula going.

PMS: I said this in one of the podcasts, an interview, I think a lot of people see that—it’s something I’ve struggled with a little bit—as weakness.

LH: Ah.

PMS: Oh, the niceness. “Oh, you’re so nice.” That you’re going to be taken advantage of. I don’t think niceness equals weakness. You can find a middle ground. I’m not a pushover. If somebody’s gonna fuck with me, I’ll give it back to you but I will always treat somebody with respect at first. Always. I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt. It’s up to you at that point to reciprocate or not. I won’t ever fuck with somebody—I don’t mean I’m gonna go make their life hell—I’ll just Block you. I don’t need that negativity.

Being an artist, as you know, being a creative person, being a writer, there’s a fine line between criticism and feedback and then negativity. There’s a lot of people you see the back-handed compliments or the people who are just dumping something on you. I’ve found that at this stage in my career, I don’t need it. I don’t need any negativity. I’ve got my own system going here, and if you’re going to be that way I’m gonna Block you. I’m never gonna give you the light of day. [Laughing]

Mentors, Signal-to-Noise Ratio and the Abundance Mindset

LH: Right, and the amazing thing to me is that your kimono is wide open. You’re saying, “These are the processes that I’ve learned and refined, and you can follow in my footsteps.” For example, you mentioned in the interview with Scott Meskill that your most popular podcast episode is the one about navigating different online art marketplaces. [Episode 9, “My Favorite Online Art Marketplaces”] When I was listening to that, and I’m not a painter, but I am definitely embedded in marketing my creativity, it occupies a lot of my waking time and thinking. I said—I’m getting goosebumps right now—because if I was a painter and you told me the things that you say in that episode, I would have literally transcribed every word. And started a three-ring freaking binder and chapter-ized the thing and said okay, I’m on Chapter 2, Preston, okay, what did he do next, and just bang, execute. Because there aren’t a lot of mentors out there.

PMS: No.

LH: There’s a lot of noise, man. Online is a quagmire of noise. It’s a signal-to-noise ratio problem.

PMS: Definitely.

LH: You’ve risen above the noise level because not only do you have the consistent body of work, but you have a willingness to share with other artists. To say, “This worked for me. Try this on. We can even have a discussion. You may wish to do something different. Hallelujah.”

PMS: Yeah.

LH: There’s an exceptional graciousness about what you’re doing by letting people in on what’s been working for you and I think that’s really commendable.

PMS: Thank you. I think that was a big thing for me too, is discovering the abundance mindset. It’s a simple concept but it’s really hard to put into practice. I think a lot of artists feel like resources are finite. They feel like attention is finite. They feel like if their fellow artists, even in their same genre, let’s say you do drip paintings, or you do fluid art. Well, if this artist on the same marketplace is selling their work well then I’m not going to be able to sell my work. That is so false. Once I started transitioning into knowing that there is so much money out there, there’s so much attention out there, there’s room for so many people to have success. What you’re doing when you’re being jealous about somebody else having success is you’re basically shutting off your own success.

When I’ve been able to feel actual jealousy—and I still have it—you have a bad day, you have some dark times. The jealousy, I’m not gonna lie, it still comes in from time to time for people that I really admire. But for the most part I’ve become a person where I’m genuinely happy and excited for another artist when they make a sale, and it has nothing to do with me, it doesn’t reflect on me. We as artists and creative people, we have to be a little bit self-involved. Because who would become an artist if you’re not trying to expose something about yourself for the public to digest. You have to be a little bit self-important to be in this game. When I finally discovered that your success, not only does it not take away from my potential success, “the rising tide lifts all boats” mentality, you know? If they can do it, I can do it. If I can do it, you can do it. Yes, there has to be some level of talent, but assuming you’re going towards honing your craft, you can also have success.

PMS: Now even more so with social media. You can get lost on there, and FOMO is definitely a real thing. Seeing other artists doing all these great things can detract from what you’re doing. I know for some people it takes the air out of their balloon. They get on social media and they feel like their life is meaningless. Whereas now my trick is to create something myself, always be creating, so when you go on social media it’s not taking away from what you’re doing.

It’s like a “Yes, and…” prompt in improv, instead of blocking the other person where you say, “Oh this is a tree,” then your acting partner says, “No, that’s not a tree that’s a boat.” Scene over! You just blocked that person. It’s the same concept with this. If you go on social media when you wake up in the morning and you start looking at this waterfall of artists and all the things they’re creating and the amazing experiences they’re having and they sold here and they’re at this gallery here, you don’t even want to get out of bed! But if you have already started your day, you’ve created something, you’ve put something yourself out in the world, you can look at social media with a different set of glasses. All of a sudden it’s like, “Yes, I did this, and you’re doing this.” That can be powerful.

It’s also a healthy level of competition. I think it’s okay to be competitive. Not being jealous doesn’t necessarily mean you have to not be competitive. I look at these people and I’m proud of them and I’m happy for them and I’m also comin’ to get ya. [Laughing]

LH: Yeah! I played tennis for a while in high school and I always played my best tennis with people that I knew could crush me. But I would expend that 120% to get that one cross-court shot that they didn’t see coming. Done! I’m happy! Cool!

PMS: Exactly. And also you get better that way.

Block the Nay-Sayers

LH: You do, you definitely get better. There’s this phenomenon that you were speaking about, being proactively creative. Sometimes I get annoyed when people say, “Hey, what are you working on now?” or “What’s coming out next?” or “When’s that sci-fi novel gonna be finished?” As though I have some prescribed requirement to explain. I don’t know what that is! Is that a variation of a theme that we’ve already talked about? It’s not like a tortured artist. It’s more like, do I really have to affirm myself through your approval of what I’m doing next? What is that, Preston!?

PMS: Right! This is great, because everybody deals with this. It’s the same reason why I don’t tell certain people any more what I’m doing. What used to happen was, I would have a great opportunity, I would have a gallery show, I’d be doing some amazing event that it’s foolproof that you’re gonna go in there and knock it out of the park. Without fail, every time it would be done, certain people would say, “Hey, Preston, so didja sell anything?” Then you fall back into the old, “Well, no, I didn’t sell anything but it was a great opportunity, da da da da da.” It’s like it’s only valid if you’re selling. It’s only valid if you’re creating something else. If you’ve got something else in the pipeline. I think it’s people projecting their own insecurities on you. It’s another function of haters, nay-sayers, it’s a way of sounding like you’re being positive while you’re actually getting a dig in. It’s like a back-handed compliment.

LH: Passive aggressive!

PMS: It’s very passive aggressive. I’ve gotten so much of this, and I just call people out on it now. I had a friend who used to do that to me all the time. “You know what, so-and-so, I’m trying to cultivate a very positive environment here. I know you mean well, but when you say this it makes me feel like this.” Immediately, luckily this person was, “Oh I’m sorry, I’m so proud of you,” and I said, “Well, in the future let’s just keep it positive.” It’s a dig. It’s to deflate your balloon.

LH: They are perhaps speaking from a perspective of, “I wish I could have some achievements.” Trying to pull someone else down so that they might feel…

PMS: Without looking like a complete douchebag. If you were on the outside, you’d read that social media comment, it’d be like, “Oh, okay, that’s a valid question,” but you can only understand the depths of that as a person who’s creating.

LH: I feel lighter, Preston.

PMS: My wife and I have gotten very good at not paying attention to these people. Don’t even answer them.

What’s Up Ahead in the Art World?

LH: I’m going to keep pivoting… Let me get your thoughts on what’s around the corner for the art world? Because you are being proactive with your radar. You’re looking ahead. You understand color, texture, beauty. Those things are important to you. They are a constant, so there’s always going to be an interest in an exploration of your work with those axioms. But what do you see coming in the next one to two to five years in the art world as it would affect an artist such as yourself?

PMS: As much as it doesn’t seem like it, we’re still in the beginnings of the Wild West of the online art world. Covid has been like a shot of steroids. Everybody all of a sudden is, “Online online online, virtual shows,” and now it’s gonna flood this market too. I’m already seeing it. They’re saying record-breaking art sales online since the pandemic started. It’s obvious why that is, because you can’t physically go into a gallery now, so of course those people who still want to buy art are going to buy it online. But is it going to transition back into somewhat of a balance? I think somewhat, but it’s going to be heavily weighted towards online from now on. And it’s gonna flood the market which means we all have to adapt.

What I’m going to do is—my whole fear is that it’s not sustainable, up to a certain point. Whether that’s a year from now, five years from now, ten years down the road. I’m grateful that I’m able to do what I’m doing right now. But it’s not sustainable for me to work seven days a week, every day marketing my shit and putting my work up online every day and breaking my back every single day for seven days a week, sixty hours, seventy hours a week until I’m sixty, to just be making enough painting sales to get by. I’ve always got ideas…

LH: You don’t have to give up any secrets!

PMS: I’ve got some cool things in my mind and down the pipeline as far as what I’m going to create. My goals shifting forward, why do actors become producers and directors, right?

LH: Hey, okay. Yes!

Expanding the Radius

PMS: I’m always going to be an artist and I’m always going to create. But I’m also looking for ways to be somebody who can influence and have a greater influence. I’m not just a guy who’s online making a sale here and there. With the podcast, for example. That’s influential. You can reach a wider audience that way. You can help people by creating value. But also, it does get reciprocated. The more value you’re creating, sometimes it comes back to you. I put it out there. I create value and then I leave it open to how it’s going to come back, and that’s fine. And if it doesn’t come back, I still loved doing it so that’s great.

But I’m also doing these things like the YouTube channel (PMS Artwork), the podcast, I’m doing these shows at ShockBoxx. I’m also going to be ramping up my creation and creating bigger pieces. And I’ve got a couple of ideas for some more commercial stuff that I’m going to be doing, as well as some stuff that’s completely creative and not something that can be perceived as being aware of how it’s going to end up in the marketplace. I’m like an investor right now. I’m diversifying my portfolio.

LH: Brilliant. Yes. Asset allocation!